Chinese celadon, with its serene, jade-like green glaze, is perhaps the most iconic and revered type of East Asian ceramic. Far from a simple pot, a celadon vase is the result of a precise, centuries-old alchemy, blending earth, mineral, and the intense heat of the kiln.

Originating in China during the Shang and Zhou dynasties, and perfected during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) by kilns like the famous Longquan in Zhejiang province, the creation of a celadon vase is a multi-step process demanding exceptional technical skill and control. It’s a journey from rough clay to lustrous, translucent artistry.

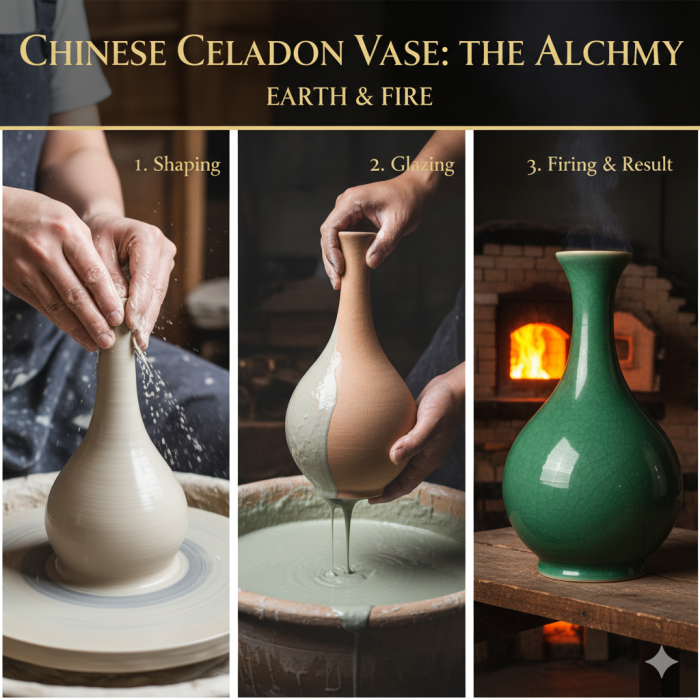

Here is a detailed, step-by-step breakdown of how a traditional Chinese celadon vase is created:

Phase 1: Preparing the Clay Body (The Foundation)

The quality and color of the final celadon glaze are heavily dependent on the ceramic body beneath it.

1. Sourcing and Preparing the Clay

- Material Selection: Traditionally, Chinese potters used local stoneware or porcelain-type clays. For the finest wares, a high-quality clay body—often low in impurities like titanium—is essential to prevent a dull or yellow tint in the final glaze.

- Wedging and Purification: The raw clay is meticulously cleaned, mixed with water, and thoroughly wedged (kneaded) to remove all air bubbles and achieve a perfectly uniform consistency. Air bubbles can cause the vase to explode during the high-temperature firing.

2. Shaping the Vase

- Wheel-Throwing: The clay is expertly thrown on a potter’s wheel. Master potters achieve remarkable thinness, balance, and the elegant, classical shapes associated with celadon—such as the meiping (plum vase) or the yuhuchunping (pear-shaped vase).

- Trimming and Drying: Once the form is set, the piece is carefully trimmed to refine its shape and create a stable foot-ring. It is then allowed to dry slowly and completely until it reaches a leather-hard state.

Phase 2: Decoration and First Firing (The Biscuit)

Unlike overglaze decorated wares, celadon’s beauty often lies in its subtle decoration, which is applied before glazing.

3. Carving and Incising (If Applicable)

- Underglaze Decoration: Many fine celadon pieces are decorated with subtle designs—such as floral patterns, stylized waves, or dragons—which are carved, incised, or molded into the leather-hard clay body.

- The Glaze Effect: This decoration is critical because the thick celadon glaze will pool in the recesses of the carving, creating a variation in color depth. The recessed areas appear a deeper, darker green, while the raised areas are lighter, enhancing the three-dimensional quality of the design.

4. The Biscuit Firing

- The raw clay piece, now called “greenware,” is placed in the kiln for a low-temperature firing (around 800∘C to 1000∘C). This process, called biscuit firing, hardens the clay, making it porous and easier to handle for the next crucial step: glazing.

Phase 3: Glazing—The Secret to the Jade Color

The distinctive jade-green color is not paint, but a chemical reaction within a unique glaze formula, applied before the final, high-temperature firing.

5. Celadon Glaze Composition

- The celadon glaze is a specialized, high-fire feldspathic glaze. Its key to color is a tiny amount (typically 1–3%) of iron oxide (or ferrous oxide, FeO).

- The mixture also includes materials like feldspar (flux), quartz (silica), and limestone or wood ash, all finely ground and mixed with water to form a liquid suspension.

6. Applying the Glaze

- The porous biscuit-fired vase is dipped, poured over, or sometimes sprayed with the liquid celadon glaze.

- Crucially, the glaze must be applied thickly. The opulence and depth of the celadon color are directly related to the thickness of the applied glaze layer. Multiple layers are often applied, with time allowed for drying between each coat.

Phase 4: Reduction Firing (The Final Transformation)

This is the most challenging and pivotal stage, where the chemical reaction that creates the jade-green color takes place.

7. The High-Temperature Firing

- The glazed vase is placed in a specially designed kiln (historically, a dragon kiln or climbing kiln). The temperature is slowly raised to a high-fire range, typically between 1250∘C and 1310∘C (2280∘F to 2390∘F).

8. The Critical “Reduction Atmosphere”

- The final, beautiful green is achieved not just by the iron, but by manipulating the kiln’s oxygen level in a process called reduction firing.

- How it Works: Once the kiln reaches a high temperature, the oxygen supply is deliberately restricted (often by damping down the air intake or adding organic material like wood). The fire, starved of oxygen, begins to draw oxygen from its only available source: the metal oxides within the glaze.

- The Chemical Change: The ferric oxide (Fe2O3), which would normally produce a dull yellow or brown color in an oxygen-rich (oxidation) firing, is chemically reduced into ferrous oxide (FeO). This chemically altered iron oxide is what magically imparts the signature soft blue-green, jade-like hue to the glaze.

9. Cooling and Unveiling

- After the peak temperature and reduction period are held for the required time, the kiln is allowed to cool very slowly. The slow cooling process is essential for the glaze to mature fully and for the desired color and texture to lock in.

- The final opening of the kiln is a moment of anticipation, revealing the finished celadon vase, now transformed into the timeless “green ware” that has captivated collectors for over a millennium.

The Enduring Legacy

The creation of a Chinese celadon vase is a poetic balance of form and function, clay and chemistry. The subtle variations in color—from pale fenqing (powder blue-green) to deep meiziqing (plum green)—are all down to minute changes in the glaze recipe, firing temperature, and the exact timing and intensity of the reduction atmosphere.

This complex, ancient process ensures that each celadon vase is a unique piece of history, reflecting the mastery of the potter and the elusive, jade-like beauty born from the intense embrace of earth and fire.